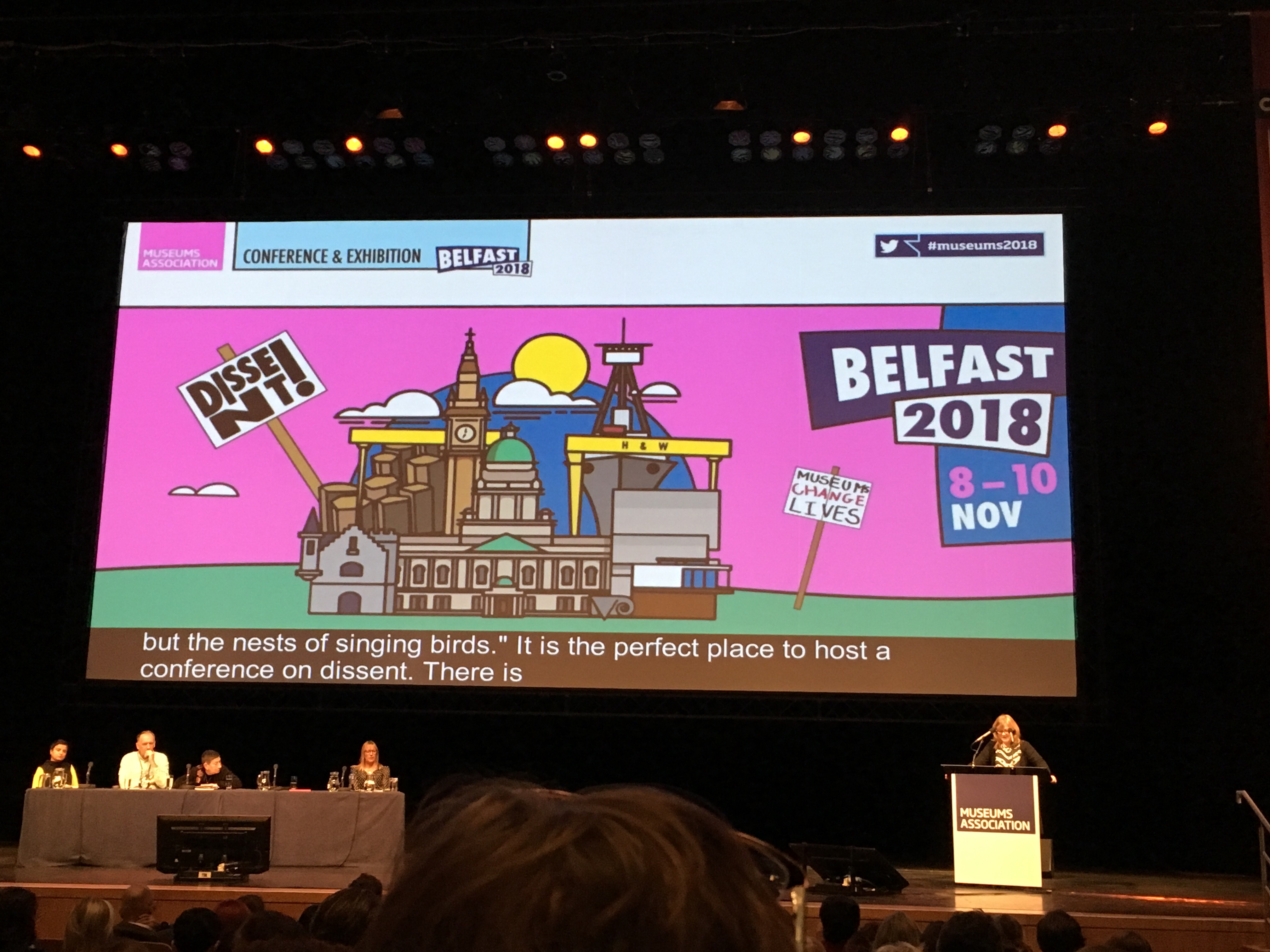

I’ve just got back from 5 days staying in Belfast for the excellent dissent-filled Museums Association Conference 2018. It was my first visit to the city, and indeed to Northern Ireland, and it has, just as its title suggested, inspired both hope and change on a personal as well as professional level.

I would like to say a huge thank you to the Museums Association for awarding me a Trevor Walden bursary (to Sarah Briggs for drawing my attention to this, and Tamsin Russell for organising it), which enabled my attendance. It seems fitting to read about Trevor Walden himself, a man who, amongst various accolades was instrumental in establishing my alma mater, the School of Museum Studies in Leicester while running the museums service there. I would also like to thank everyone at the Museums Association – its staff and team of volunteers – and the helpful, friendly and patient staff at the Belfast Waterfront Hall– for their hard work, and of course thanks too to all speakers and fellow dissenting delegates.

Belfast. What a city for a conference on the theme of dissent! Roisin Higgins, our conference host, introduced Belfast as a place that ‘breaks your heart’ – but also as a place of ‘creativity, joy and courage’. In my short time there, I found all of this (and much more).

Here, in no particular order, are some of my initial reflections: on the city, on dissent, on the conference, on my learning, and on my hopes for the future.

MA Conference 2018: Welcome

Belfast: City of culture

Staying at the Easyhotel was a great find, as its helpful manager, passionate advocate of the city, Kevin, used to be Head of HLF for NI (!) and was full of tips, perfect for a museum geek. As well as a packed conference timetable, I also used my time in Belfast (Weds-Sun) to actually get to know the city a bit. I really had no idea what I’d find – no idea that the city was surrounded by beautiful purple hills and rocky outcrops. Even in what felt like the bleakest parts of city, the countryside – and freedom – beyond, was very present.

Expressions of ‘creativity, joy and courage’ were all over the place in Belfast’s museums: in the Linen Hall Library where I had lunch on my first day, I got my first taste of political posters; at the stunning City Hall where we had a lovely drinks reception courtesy of the city of Belfast (and which would definitely be worth a longer visit next time as it houses a museum of the history of the city); at the Ulster Museum and its open-ended Troubles Gallery, and crowd-pulling Dippy exhibition; on the brilliant organised tours to the Crumlin Road Gaol with superb guide Terry sharing his knowledge with just the right balance of humour and trigger warnings prior to discomforting experiences (something that did not happen in a later conference session on medical collections and babies in jars which I found incredibly difficult to be confronted with, with no warning); at the Ulster Folk and Transport Museum with piglets and donkeys and a packed event for miniature railway enthusiasts; at the Titanic Experience – but equally on board its tender SS Nomadic and in the actual stunning drawing offices of Harland and Wolff (now the lovely bar of the Titanic Hotel – thanks to Kevin’s recommendation!). Just listing all this is making me a bit dizzy – and giving me good reason as to why it was so tiring. I clocked 25.3 miles of walking. And this doesn’t include the miles of thinking and voice worn out from talking to lovely colleagues and friends old and new…

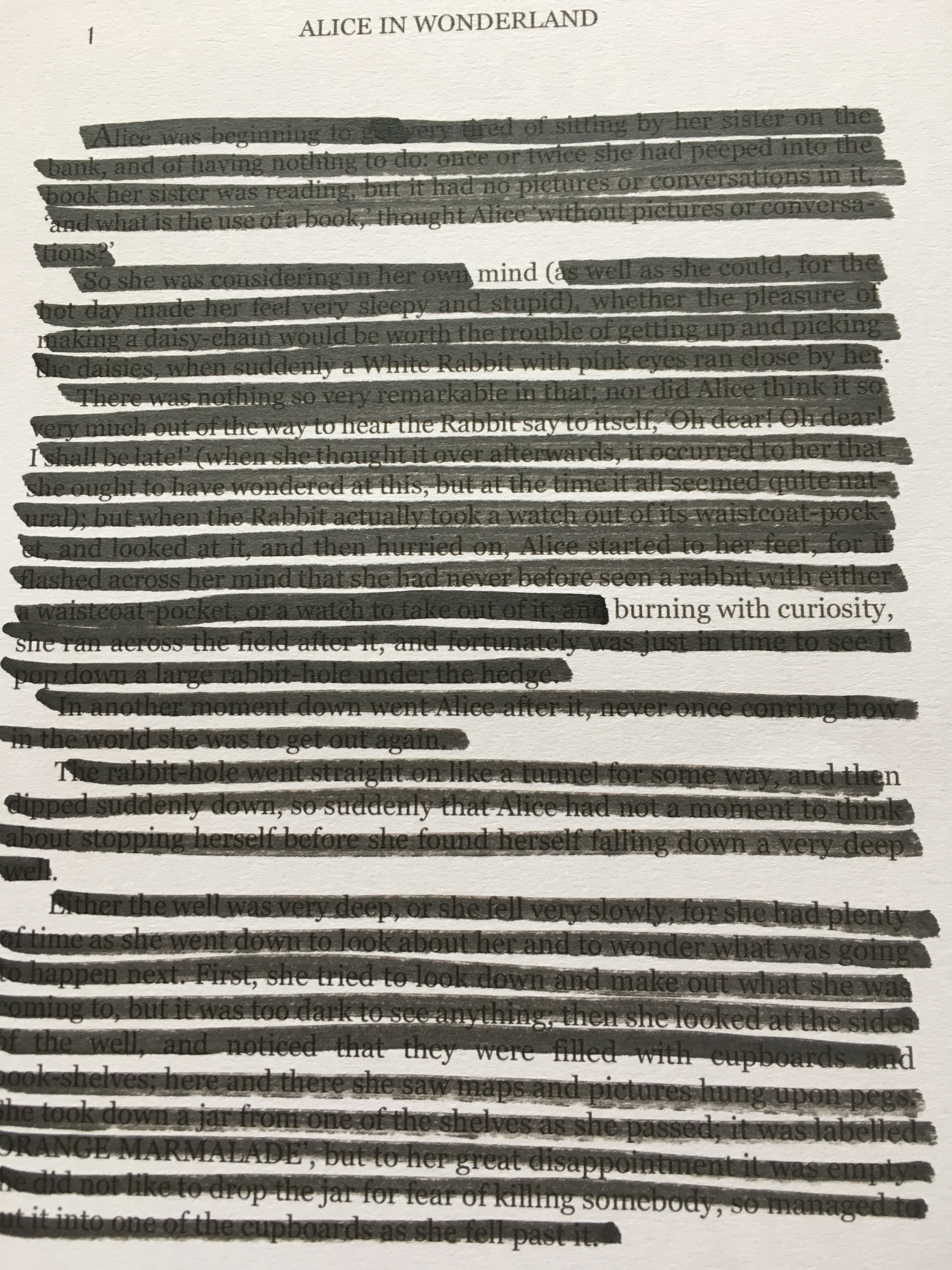

The conference was framed with the brilliant Rita Ann Higgins (on CryinAir, Belfast being ‘clean and posh’, and on guilt in Irish) and Glenn Patterson (‘up your hole’): I love the way the conference involves people from outside the sector – more of this!

Belfast: City of fragility

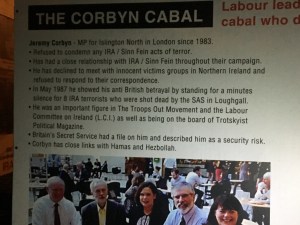

On the Wednesday, I started my time in the city with a (non conference organised) political walking tour of West Belfast. Beginning at the bottom of the Falls Road at Divis Tower, site of the death of the first child to be killed in the Troubles, we were led by former IRA member Jack. (Divis is named after a mountain, but, I reflected it could also stand for ‘division’, even now alas…) It is not every day that you meet someone from the IRA, and it was incredible to hear his perspectives. He focussed particularly on the roots of the Troubles in the civil rights movements of 1960s and as a campaign for social justice. He was also very keen to tell us that it wasn’t simply a Catholic v. Protestant thing. This part of the tour culminated in seeing Bobby Sands’ mural (whose story apparently was the first news story to ever capture my attention as a 3 year old in 1981, wondering if he’d eaten yet), and then a walk past the ‘peace wall’ – an oxymoron if ever there was one, with mesh barricades and cages over people’s gardens. I just had no idea.

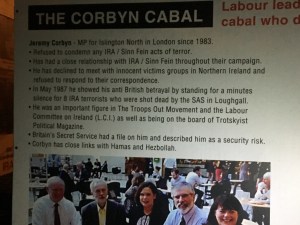

We then met the second guide, a staunch Unionist, Mark, at the gate between the two communities, which still locks at 7pm every night. I asked Jack how the tour worked, whether he and Mark were friends… No. They were professional colleagues who said hello to each other – but basically, that was that. No crossing into each other’s spaces. So then Mark showed us the sadly neglected areas off the Shankill Road. Unlike Jack, he did speak of the situation in terms of Protestant and Catholic. And we walked along the road itself, to the site of the bombing of Frizzell’s Fish and Chip shop in 1993. The poppies, the images of the Queen, the (violent) murals. I felt weirdly much more uneasy in this area, especially after seeing a memorial with text panels and propaganda demonising Jeremy Corbin, horrific images of bodies… It is all so fragile, so complicated – and so neglected by the British media and in our own education system. The whole thing left me feeling a complete sense of ignorance, of not knowing, and being let down because it is not taught. And because who knows what will happen with Brexit. Fragility.

Dissent

So to the actual conference itself. I recently wrote a blog post about being defiant. And I think that the idea of dissent shares some similarities – perhaps too with what Sara Ahmed calls ‘willfulness’. There is something necessary about being willing to dissent – to be opposed to the prevailing idea – for democracy, and because usually this is connected with unequal hierarchies of power: inequality. But when does a dissenter become a dissident? A question for us all, but absolutely central being in Belfast, in Northern Ireland, amidst all the turmoil of the Troubles. And what happens when dissent does not bring about the radical change it aimed to do? Or when everyone is dissenting but in different ways without a unified cause – or with ‘opposite’ causes? Or with violent ones? The idea of how we tolerate the intolerant is bound up in all this, and was a strong theme throughout the conference. How do we include people that we hate and fear within our spaces? Should we?

Three dissenters were there throughout the conference: Elaine Heumann Gurian, Paddy Gilmore and Sara Wajid. (I’d met Elaine some years before, and was reminded of one of my Leicester PhD colleagues from Germany telling her then that she was ‘so old’ (she’s inspirational at 81!) – meaning to reflect that she was ‘so experienced’, but it got lost in translation and made us all, including Elaine, laugh a lot!). Elaine situated herself as a German Jew from America, completely unprepared for the horrors of Trump. Strangers seeing each other in public places is, for her, the bedrock of peace. Paddy, in NI, talked about needing to know one’s values – and moral core, and that it takes courage to say when you dissent. Sara talked of her experiences at BMAG, bought in as ‘commissioned dissent’: it is hard to make change as an insider, but that so often people are brought in to make change when an organisation is not ready or willing to be changed. Can a museum ever be decolonised? How can we provide positive conditions for provocation? ‘Dissenters generally don’t get sent to conferences’, was one of Sara’s comments that has stuck with me: it is a rare thing to have power to actually effect change…

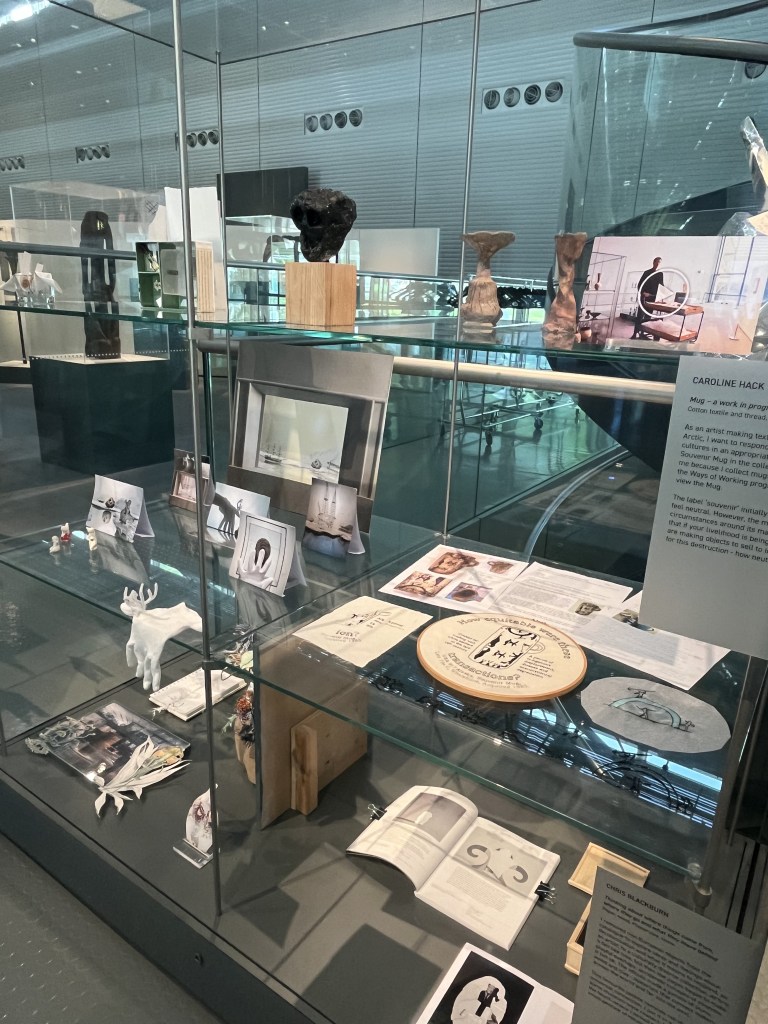

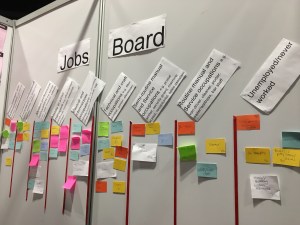

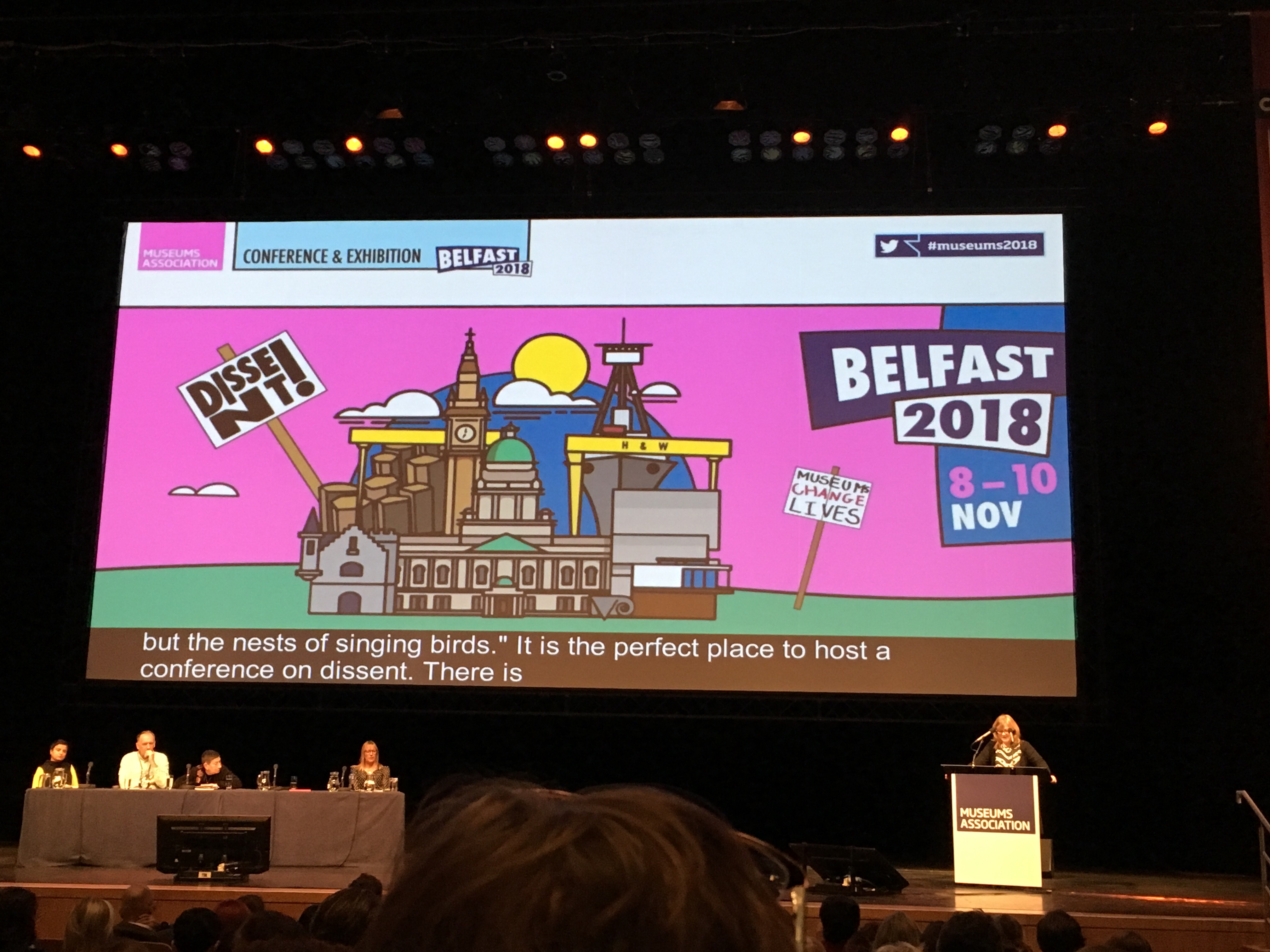

Festival of Change

I completely loved the Festival of Change (although it is still positioned at the peripheries of the conference, and I’m not sure about this… Museum as Muck, the Vagina Museum, the Museum of Dissent, the Museum of Femininity – perhaps all of these could/should have had a central stage – although I also really like the fact that they don’t – that they are just there and in everyone’s face…) But as well as loving the Festival of Change, it left me very uncomfortable. Discombobulated. And it left me reflecting that actually this is the very best state I could have left in: because it is when we feel uncomfortable about a thing that we need to do something about it. Dissent. I don’t identify as working class, but the Supermuckers’ (@museumsasmuck) shop and jobs board sticks in my head and left me with lots of questions about class and injustice and privilege and entitlement, that are very difficult. I left pledging to tell people about their work, to donate to Arts Emergency, and to ensuring that class and inclusive practice is absolutely part of volunteering, recruitment, and board processes. And I came across something to read: the Panic Report. At the Museum of Dissent, where only the curator was allowed to impart the actual ‘factual information’, we looked at the challenges of (teacup) labelling in a ‘reverse’ anthropology – where ‘the accompanying tealeaves are of particular importance to the natives of the isles and cause the nation to be at a constant tipping point’ with civil unrest between the PG and the Yorkshire clans (!); at the Museum of Feminity there were sensory exhibits with instructions: touch me, smell me, insert me, taste me… at which I learnt more about how to do a breast examination than I ever knew before (using a commonplace silicone boob used in USA schools), that contemporary smelling salts are not to be inhaled deeply, and suggested an addition of a moon cup to the collection; at the Vagina Museum I struggled to label all the parts of a clitoris and loved the (b)unting. This could definitely be a new festival line. In fact, the whole conference did feel like a festival: that mixture of there always being something to do, while there’s also something else equally exciting that you could be doing.

Museums are not neutral

And neutrality is not neutral anyway. I don’t have the t-shirt, but there is one, and it is doing a roaring trade. I loved Laura Raicovich’s keynote on this theme: in particular that she’d resigned from her post as Director of the Queens’ Museumin the most diverse area of New York because of frictions between her inclusive values and those of the board of trustees. Taking inspiration including from liberation theology, and other civil movements, she talked about Art Space Sanctuary– a place for us to declare our spaces as sanctuaries and safe public spaces for all people regardless of race, gender, ethnicity, immigration status, sexuality, religion, politics etc. And yes, this is absolutely right and positive and good. But again there was that question: who decides what is or is not appropriate? Where is the boundary between promoting a set of values (of inclusion), but including those whose voices we don’t agree with too? How can we be political but not partisan? I’m not sure I have the answer to this yet (and maybe if anyone did, the world would be a whole lot more peaceful). And just as museums are not neutral – neither are we… So we have to take a stand.

Knowing your values

I think for me, thinking about, and trying to define my own values has been the strongest and most important thing to come out of the whole conference. I was lucky to have been allocated a coaching slot as part of the careers development element, and spent a very useful, hopeful and change-making hour with coach Louise Emerson from Take the Current. So I was already immersed in thinking about what makes me tick (and what I want to make me tick) when I went to Janneke Geene’s hosted session, led by gurus Hilary Carty, Richard Sandell and John Orna-Ornstein, on ‘values-led practice in troubled times’. Janneke began with a comment that our work is (and has to be) an expression of our values. Having recently left a job because of this, this was a deeply moving and important session.

Hilary began by listing her values – bish bash bosh – as easy as that! (Except I’m sure it was not easy.) For her, to be true to herself is about 1) integrity, 2) generosity and 3) curiosity. Those are her key values, from which all else arises – mingled in with the need for self-care. If we are going to challenge things, we need to look after ourselves along the way. Yes. Richard and John then talked about the Prejudice and Pride project – how Richard participated in Exeter Pride with the National Trust’s rainbow banner, with all the spectators saying ‘OMG it’s the National Trust’! The Kingston Lacey project came post-Felbrigg and culminated in a debacle over whether or not the rainbow flag could be flown from the rooftops in Dorset. I completely admired the absolute honesty of the speakers in this session: opening themselves up to really talk about how it was for them in such a generous and trusting way.

I’ve been thinking about what I value ever since, and have the beginnings of a long list – but it needs rethinking and refining, and probably turning into a useful ‘bish bash bosh’ checklist. At the moment, and in no particular order, it is something like this:

- Imagination and curiosity

- Not knowing– humility, letting go, and opening up

- Courage – to speak out, take risks, make change

- Giving – generosity, being kind and caring for people and planet

- Inclusion– connecting, reaching out, welcoming in, sharing

- Equality and justice– for people and for the planet

- Body/mind/spirit– materialities, embodiment, senses, emotions

- Doing and thinking– research and practice as intertwined

One other thing I have done post conference is to write a list of all the people I had conversations with, the people I didn’t have conversations with but wanted to, and the people I want to send follow-up emails to as a result. I love networking. Writing a list though is something I haven’t done before. It took a while but I think will be useful. (The app was brilliant, including for this).

Engagement

There were lots of sessions that dealt with amazing community projects as always, but here I’ll just look at what engagement looks like in the digital realm. Martin Grimes, my former colleague and web manager at Manchester Art Gallery kicked off thinking in this vein with his open and honest talk about #nymphgate, and how the gallery simply wasn’t ready for the storm post Guardian articles following the arranged feminist take down of Waterhouse’s Hylas and the Nymphs by artist Sonia Boyce. He started with an image very familiar to me from the Mary Greg project back in 2008. But rather than talk about this project as having been a good way of engaging people (which is the language I usually use, as it opened up the stores for rummaging by members of the public), he used it to talk about its digital presence in a more negative way: basically one of broadcast, rather than engagement. The old problem of didactic learning rather than any other sort of constructed and open ended learning. We are, he said, on the whole, pretty good at engaging with people within our museum spaces; this is what learning teams do brilliantly. But this is still not so in the digital world. Often people dealing with social media have nothing to do with the learning team. Not quite hiding under their desks, Martin described how the team at MAG ‘lost control of the message’ and by the end were ‘not even sure what the message was’ (interestingly this debacle coincided with a lack of director, and an absent deputy director). PhD student Maria Arias then talked about how she’d been able to keep track of these Twitter conversations for her PhD research using free software TAGS, a very useful practical piece of advice. The discussion post-session was one of the most lively and honest in the conference. The closing comments by one delegate was that the whole scandal was nothing to do with the content, but it was about a pattern of voicelessness in the world. People in the current climate do not feel they are heard, but they do have a voice and so shout on social media. How do we as museums deal with this – giving space and a voice?

Opening up and letting go

The session on digital engagement was followed by absolute unit legend Adam Koszary from the MERL and his now infamous big sheep, soon followed by chicken in trousers – see his write-up here. Again, Adam talked about the distinction between broadcasting to people, and actually engaging people online. For me, the key to his presentation though was around knowledge of the collection. In order to open up the collection, to let go of it for people to engage on their own terms (which surely is what we all want – and what, had I been to the session on Collections 2030, I might have heard more about – alas a regrettable clash), we do still need to know our stuff. Don’t just put a picture up and tell people what’s in it, but make stories, embrace experimentation, allow people to take it and do as they will, grounded in what is there. Social media can only be used for debate, dissent and dialogue when it is treated as an engagement tool, not as a marketing tool. Yes. Social media should not just be done by marketing (unless they are skilled in communications and engaging with all audiences). It reminded me of the debates raging almost 20 years ago about digital in museums: ‘digital is not a department’ – everyone needs to embrace it. No department is a silo. Twitter at the MERL works because they know their stuff and engage people with it, with good humour as a way in. (Incidentally, I’m loving this week’s cock-related liaisons avec Le Louvre).

I enjoyed hearing Chris Rolls talking about his project 64 million artists. Everyone is creative. An office of just 3 staff members had the task to develop digital resources for everyone to develop their own creativity. These can be found on DOTHINKSHARE. Interestingly, I think this was the only time during the conference that I heard ‘by, with, for’ (almost the ‘ofbyfor’of Nina Simon). And it was chaired by Ross Parry who is always generous and worth hearing as much for presentation/chairing style tips. But there were questions: yes, we can let go and give things over to online publics, but is the digital ever really democratic, when so many people do not have it or use it?

Mendoza

It is a year since I read and wrote a blog on the Mendoza Review on my way to the 2017 conference in Manchester. So it was interesting to be in a room – a very ‘top heavy’ room (with some comments that made me squirm and feel that there’s such disparity even within the sector – its ‘elite’ versus its own ‘muck’), with Neil Mendoza, Ian Blatchford and Laura Pye, sharing their thinking a year on. One positive discussed, was that the ‘HLF/ACE peace agreement’ had been signed. But Laura Pye said it as it is: recognising that the panel was not a diverse/representative one, and that the report did not do enough. That there is a crisis in the sector: funding, diversity, collections management and relevance. She talked particularly about funding. Her view was to support a mixed model of funding – including introducing a tourist tax – £1 per night per room would generate more money for culture than the whole current culture budget. Another pot would be the ‘cultural development fund’ – which would stop local authorities making a choice between health and culture for example. Sounds like a good idea. There’s a huge difference, she pointed out, between just surviving (as per Mendoza) and really thriving (as per the good old days of Renaissance). All panel members talked about the need to better articulate what it is we do – but particularly the difference that we make. And so it continues…

Hopes

Elaine ended the conference by saying she wants museums ‘to be forces for peace’. Maybe this is why we are all in it. Seeing people’s humanity is the first step in forgiveness. Vital in a city like Belfast. And this made me glad that I’d started the conference off by meeting and listening to Jack the republican and Mark the unionist in West Belfast. My hope is that one day they will go for a pint together.

If you’ve got to the end of this, well done! And thank you again to the Museums Association for supporting me to attend a brilliant conference.